1. What is a continuity? What is a discontinuity?

A continuity is a function that is predictable, has no breaks in the graph, no holes, no jumps and can be drawn without lifting your pencil.

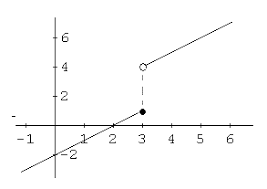

A discontinuity is distinguished in two different groups: removable discontinuities and non-removeable discontinuities. There is only one discontinuity known under the removable one which is called the point discontinuity. At the point of the open circle on the function, it is known as a hole, while the other point (which is closed) is on the same vertical line near it.

(http://image.tutorvista.com/content/feed/u364/discontin.GIF)

As for the non-removable discontinuity, there are three known as the jump discontinuity, oscillating behavior, and infinitie. In a jump, it's exactly how's named. The graph jumps from one point of a function to another. However, we need to keep in mind that an open/open and closed/open circles work, however closed/closed do not.

(http://web.cs.du.edu/~rjudd/calculus/calc1/notes/dis6.png)

In an oscillating behavior, there are wiggly lines.

(http://web.cs.du.edu/~rjudd/calculus/calc1/notes/dis3.png)

For infinite discontinuities, it is known as an unbounded behavior that occurs when there is a vertical asymptote.

2. What is a limit? When does a limit exist? When does a limit not exist? What is the difference between a limit and a value?

A limit is the intended height of a function. A limit exists when the same height is reached from both left and right hand limits. It also exists when a grpah does not break at a given x-value. Last, it can also exist if your ultimate decision is a hole in the graph (point discontinuity). However, a limit does not exist when there are different left and right hand limits (jump discontiuity). It also does not exist when it is unbounded because infinity is not a number. Last, it doesn't exist when it doesn't approach any single value. The difference between a limit and a value is that a limit is the intended height of a graph while a value is the actual height. When you look on a graph, it can be represented by open or closed circles. Most of the time, the intended height will be represented with open circles while the actual value will be with closed circles. However, remember that a limit and value can be at the same spot on a function!

(http://curvebank.calstatela.edu/limit/grid3.gif)

For example, from this graph we know at x=2, that the INTENDED height is 3, however the actual value is 2.

3. How do we evaluate limits numerically, graphically, and algebraically?

Numerically- We can evaluate limits numerically with a table. By having our given middle value, which we can take from the "x approaches a number", that number will be our middle. All we have to do is either add or subtract one tenths depending on which way the limit is coming from. The two answers we get will be our outside answer and all we have to do is add 0's in or 9's depending where you are. To find the value of each number, all we have to do is plug in the equation in the "y=screen" and hit graph and trace the x-values to find the actual values.

(This example is taken off the SSS packet and the template off the given one online)

Graphically- To solve a limit graphically, we will obviously need a graph. First you need to put your finger on a spot to the LEFT and to the RIGHT of where you want the limit to be evaluated. If your fingers meet, then the limit exists, however if it's does not, then the limit does not exist. This method can be the most useful because there's a visual representation of it which will help some people see it, like the points and different kinds of discontinuity.

Algebraically- When solving algebraically, there are three different "shortcuts" to evaluating your limits. The first method is direct substitution which is exactly what is says it is. You directly substitute the given value of x into the equation and solve. The four possible answers you can get are 1) a numerical answer 2) 0/# which is 0 3) #/0 which is underfined and 4) 0/0 which is the indeterminate form (this means we'll need to use another method to solve it).The second method is dividing/factoring out which can be used if AFTER direct substitution results in an inderterminate solution (0/0). All you have to do is factor out the nomials and hopefully cancel out any common terms to remove the zero in the denominator. Last, there is the rationalizing/conjugate method! Wherever there is a radical, we just take the conjugate of it and multiply it on both the numerator and denominator. The only time we FOIL is with the conjugate denominators. We DO NOT FOIL the non-conjugate denominator because it will eventually cancel out (That's what we want to do!)

REFERENCES: Unit U SSS Packet